Note: The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Azolla Ventures or Prime Coalition.

Housekeeping

Last week, I had the honor of moderating a panel about how to fund moonshot ideas in geothermal energy. The panelists were seriously out of my league. It was fun! You can watch it here if you’d like.

Now back to our regularly scheduled programming.

Climate surprises

Oops, turns out methane might be a bigger problem than we thought. Published last month in Nature Communications (emphasis mine):

We estimate the causal contributions of spatiotemporal changes in temperature (T) and precipitation (Pr) to changes in Earth’s atmospheric methane concentration (CCH₄) and its isotope ratio δ¹³CH₄ over the last four decades. We identify oscillations between positive and negative feedbacks, showing that both contribute to increasing CCH₄. Interannually, increased emissions via positive feedbacks (e.g. wetland emissions and wildfires) with higher land surface air temperature (LSAT) are often followed by increasing CCH₄ due to weakened methane sink via atmospheric •OH, via negative feedbacks with lowered sea surface temperatures (SST), especially in the tropics. Over decadal time scales, we find alternating rate-limiting factors for methane oxidation: when CCH₄ is limiting, positive methane-climate feedback via direct oceanic emissions dominates; when •OH is limiting, negative feedback is favoured. Incorporating the interannually increasing CCH₄ via negative feedbacks gives historical methane-climate feedback sensitivity ≈ 0.08 W m⁻² °C⁻¹, much higher than the IPCC AR6 estimate.

In plain English, what they’re saying is not that methane is a worse greenhouse gas than we thought, but rather that climate change may lead to more methane hanging out in the atmosphere for longer than we’d expected – also bad.

How much more are we talking? A net effect about 4x worse than we previously thought:

This approximates ~0.08 W m⁻² °C⁻¹ (ref. 70) which is about four times greater than the mean net feedback estimate given in IPCC AR6 (~0.05 positive feedback including permafrost and −0.03 negative feedback, giving ~0.02 W m⁻² °C⁻¹) but agrees within uncertainty⁷.

Had we just been screwing up the numbers the whole time? No – we just learned more about how methane behaves in a changing atmosphere. It’s not just causing climate change, it’s affected by climate change.

The study calls out a couple of causes, but a key underlying factor is the atmospheric “•OH sink,” which I think is interesting. •OH is the chemical symbol for the hydroxyl radical,1 a reactive species that exists in the atmosphere at low levels. You can think of •OH as a natural cleaner for the atmosphere, chewing up pollutants and spitting them out in less harmful form. One of the main pollutants it chews up is methane.

This study showed that wildfire emissions deplete the •OH sink. The culprit is carbon monoxide, formed from incomplete burning of biomass. When carbon monoxide enters the atmosphere, it also wants to react with •OH, and competes with methane for access to it. Here are the two competing reactions written out in oversimplified form:2

1) CO + •OH → •H + CO₂

2) CH₄ + •OH → •CH₃ + H₂O

There’s normally a balance between these two, but with extra carbon monoxide, the first reaction dominates. As a result, more methane stays intact in the atmosphere for longer, able to do more global warming. The air gets spicier.

One theme of this newsletter is that we’ve seen a bunch of climate surprises in frecent years, and we’re going to see more in the years to come. Our climate models are good, but our actual climate is wildly complex, and we’re doing unprecedented things to it. We’re bound to be surprised here and there; this is a good example.

Another theme of this newsletter is that global warming isn’t just bad, it’s also weird. Well, this one’s both bad and weird. Atmospheric methane is like a sugar rush for climate change, and we just learned that we don’t have as much insulin in the system as we thought.

Since it doesn’t seem like this is going to get better on its own, I’m glad we have folks like Spark Climate Solutions, the Global Methane Hub, and a few dozen startups working on solutions. We’ll need theirs and many more.

Crypto

It’s crypto winter, so maybe cooler heads are starting to prevail.3 Let’s wade into one of crypto’s big controversies: energy use.

Bitcoin and Ethereum, the two largest cryptocurrencies, use a lot of energy. That was news in, like, 2017, but it’s still true now. Even during a downturn, the two networks are using as much energy as major countries like Indonesia and Turkey. That’s bad for the climate since most of our energy comes from fossil fuels. Some napkin math suggests the two are now responsible for about 0.3% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Apparently, Ethereum will start to use less energy soon, but people have been saying that for at least five years. Now the official line is “~Q3/Q4 2022.” Looking forward to seeing it.

If you treat the two networks as pieces of financial infrastructure, you’ll find that they use a lot more energy than their non-crypto analogues. Take the Visa network as a stand-in for “traditional finance.” Right now, the Bitcoin network uses 1,865,398x as much energy per transaction; Ethereum 240,163x. We already have a payments network that works well and emits very little. Isn’t that outrageous?

Well, maybe? Is this new method of generating consensus, born in a whitepaper in the wake of a generational financial crisis, worth the added energy use? It depends – what do you value? I don’t hear this question discussed often, but it seems to underlie much of the crypto-energy discussion without being directly addressed. The debate appears to be about numbers, but it’s really about competing belief systems.

I think there are three relevant axes:

Traditional finance: (scam ↔ works fine)

Crypto: (scam ↔ revolutionary)

Climate: (top priority ↔ not a priority)

If you think traditional finance works fine, crypto is a scam, and climate is a top priority, then you probably don’t think crypto is worth the energy use.

If you think traditional finance is a scam, crypto is revolutionary, and climate isn’t a top priority compared to financial revolution, then you probably think crypto is worth the energy use.

The consensus in the climate tech community seems to be “not worth it.” I get that – it’s a LOT more carbon dioxide at a time when we’re trying to cut emissions. The value judgment is that climate is a top priority that washes out the other two. I mean, fair.4 Plus there’s so much obvious fraud and frivolity in the world of crypto that it’s easy to write it off as unimportant.

The consensus in the hardcore crypto community seems to be “worth it,” or “why are we even talking about this?” I can also get that – if you believe the financial system is fraudulent, censorious, harmful, etc., then financial revolution would of course be upstream of dealing with climate change. If you’re even thinking about added energy use, you might see it as a necessary evil en route to a more just world. Look at Sri Lanka and tell me you can’t see that argument.

On top of that, maybe there really is a nugget of transformational technology that hasn’t yet stood out from the noise. I hear that a lot and have yet to see it, but hey, neither did a lot of people in the early days of the internet.

There are, of course, lots of people just looking to make a buck. I suspect they fall somwehere in the middle.

Going a layer deeper: for whom and when is the added energy use worth it? You could take a bunch of positions here. Maybe it’s only worth it for vulnerable groups who can’t trust their country’s financial institutions: think >1,000,000% inflation in Venezuela; Taliban takeover in Afghanistan. But who decides who gets to use it, and how are they deciding? And wouldn’t you want the infrastructure and know-how in place far ahead of an actual crisis? It gets tricky fast. Or maybe it’s only worth it if the consensus mechanism is proof-of-stake or another energy-light algorithm, so you look to implement energy controls.

Across all of them: how would enforcement work? We have tools to evade firewalls, offshore financial centers to evade laws, and anonymity to evade social pressure. There are probably ways to figure it out, but it all sounds difficult and fraught.

So I guess here’s where I land: it seems like crypto uses a whole lot of energy compared to a system that mostly works for most people most of the time. I like that we have another option in crypto, don’t like the level of energy use and grift, and fear that we may throw out the baby with the bathwater.

In the meantime, I recognize other people have other values. Who am I to tell people not to do what brings them satisfaction, excitement, or economic security? Would I tell my friends not to take flights because of the carbon footprint? Outside of the obviously evil and illegal stuff, I don’t care much about what other people do with crypto – it’s up to them. At some level, it’s a trade: a lot more energy for an unclear amount of additional freedom. What’s more important to you?

What I really want is to live in a world of abundant clean energy, where people can go nuts and we don’t have to worry about this trade. At any rate, it seems like crypto is here to stay for a little while. So let’s accept that it’s a category of economic activity like any other and work to decarbonize it.

Google Maps

Some parts of the world flood sometimes. Unfortunately, it’s starting to happen more frequently in more places. Miami is the poster child in the US: since sea levels are creeping up, and the sun and moon and Miami aren’t going anywhere, King tides are just part of life now. In time, flooding will almost certainly become a part of life elsewhere – New Orleans, New York, Mumbai, Shanghai, and so on.

I’m here to ask the bold, hard-hitting question we really want answered: What does Google Maps do when it floods?

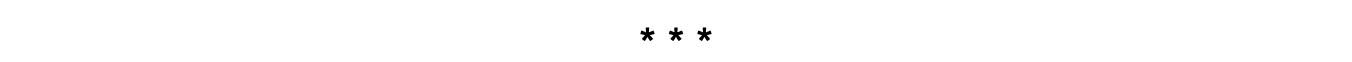

Unfortunately, we have the answer, and it’s about as banal as you might guess. They put up a notification and find you a different route. It’s no different from when there’s heavy traffic or, like, construction on your usual route to doggy daycare. It’s the techno-hell we always sort of knew was coming. See below:

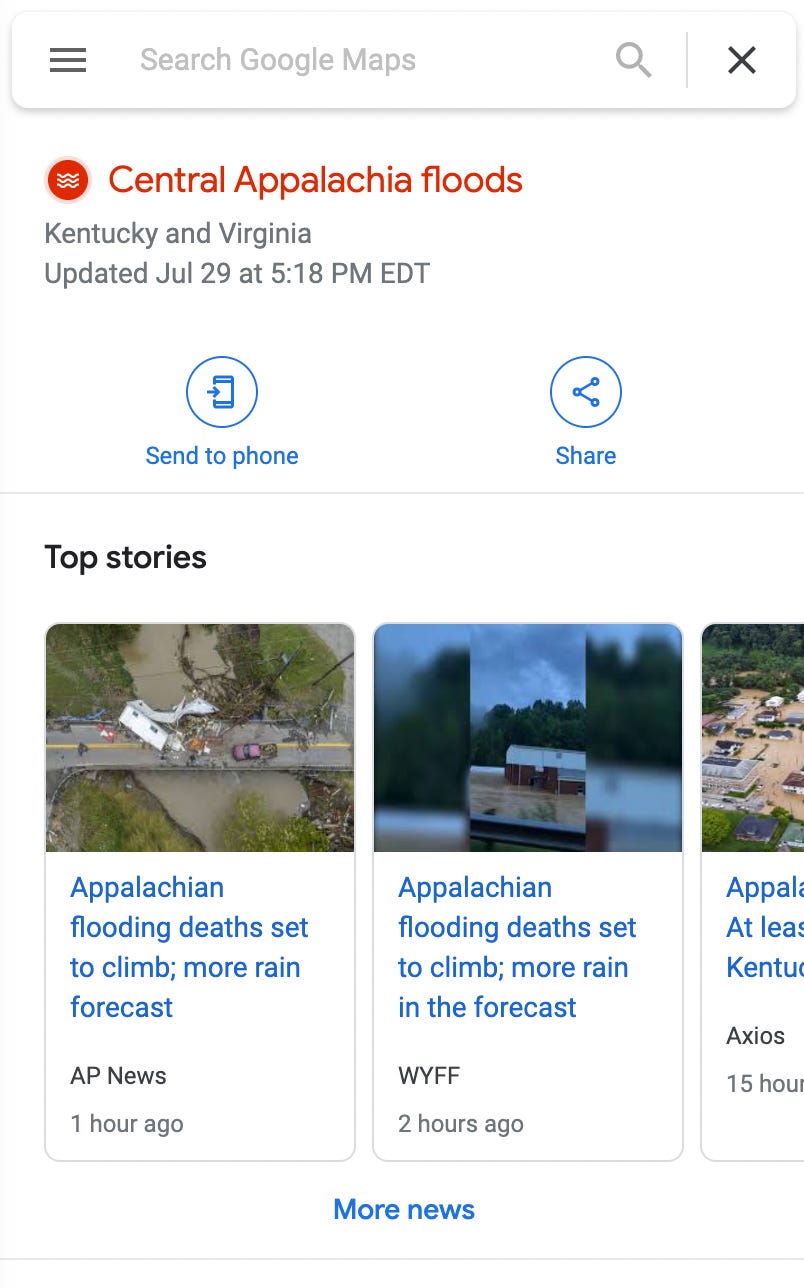

But that’s just the sanitized version on Google’s website. What is it actually doing in disaster areas right now? Because everything happens so much, let’s turn our attention to a place currently dealing with flooding: Eastern Kentucky. How’s the Google Maps user experience?

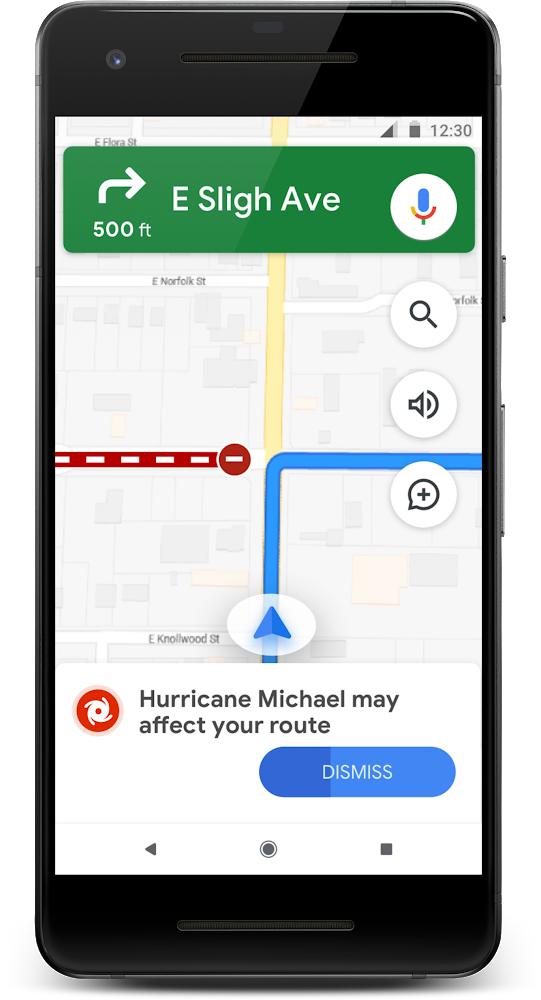

Starting at the regional level, they mark affected areas with red alerts:

Makes sense. A good starting point. When you click on an alert, a panel comes up restating the basics and linking to top news stories. Classic hands-off big tech stuff:

And then when you try to navigate through flooded roads, Google just… calmly routes you around them. Sorry, no pit stop at KFC this time:

All in all this feels pretty anodyne, and I guess why shouldn’t it? Google Maps is just a tool that helps people get around. It has to handle lots of corner cases, and one of those is flooding. It’s starting to handle other climate-related corner cases too, including wildfires and hurricanes.

But here’s what I can’t help thinking about. When the tech industry started interfacing with the physical world, we all unwittingly agreed to a long list of things. Yesterday I got into an internet man’s car because it was a convenient way to get downtown, figuring he probably wouldn’t kidnap me because his reputation and like 30 bucks were on the line. Earlier this month, a TikTok meme about a kids’ movie caused thousands of teenagers to overwhelm theaters, even leading to a riot or two. We live in a funny world.

But creeping up on that list of things we agreed to is an uncomfortable truth: Google Maps is climate adaptation. It’s how we navigate a changing physical world; it’s one of our last lines of defense against natural disasters; it’s one of the only direct interactions with climate change that many people will ever have. How do I get out of here?

That’s a lot to ask. Let’s hope they’re up for the challenge, and let’s disrupt them if they’re not.

Elsewhere:

Thanks for reading!

Please share your thoughts and let me know where I mess up! You can reply directly, leave a comment, or find me below:

LinkedIn (if you’d like to connect, let me know this is how you found me)

The “•” signifies an unpaired electron, which means that (*skips through most of general chemistry*) the molecule is very unhappy and raring to do some chemistry.

•H and •CH3 also go on to do other things. Let’s put them aside for now.

Lol who am I kidding? RIP my inbox. :)

For completeness, there’s also a climate + crypto community, which tends to focus on creating financial incentives to do good things for the climate, like price carbon or conserve land.