Note: The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Azolla Ventures or Prime Coalition.

Climate surprises

One theory I’ll start testing here goes like this:

Climate scientists are some of the most rigorous people out there. Your favorite scientist’s favorite scientist. They study complex nonlinear systems spanning several disciplines, and, amazingly, they’ve correctly predicted for decades that climate change is coming.

However, climate models can only model what’s known, and climate change is influenced by factors that are both unknown and unknowable today. We’ve already had surprises like widespread methane leaks. There will probably be others. Because of this, current climate models likely understate climate dangers in a systematic way.

Social and political pressures have not been helpful: politicization of science, threats to research funding, climate science generally being a bummer, and so on. Because of this, perhaps some climate scientists and communicators start self-censoring in subtle ways. This might mean toning down conclusions, choosing not to study certain topics, stating catastrophic findings in less alarming ways, you get the picture. Because of this, we systematically understate the climate dangers we do know about.

The combination of these two types of understatement probably mean that we’re in for some nasty climate surprises.

There are lots of counterarguments to this theory. Here are just a few:

Our understanding of climate change is actually pretty good;

Climate scientists are generally a self-selecting bunch who are unlikely to back down in the face of political pressure (some are even tenured!);

Systematic understatements of what we don’t know could be offset by systematic overstatements of what we do know;

The media ecosystem is incentivized to overstate, not understate, climate findings;

The US political ecosystem isn’t everywhere;

US R&D spending in climate-related fields has mostly been fine.

And yet, look around, we’re getting surprised. Per Reuters in July 2021:

The list of extremes in just the last few weeks has been startling: Unprecedented rains followed by deadly flooding in central China and Europe. Temperatures of 120 Fahrenheit (49 Celsius) in Canada, and tropical heat in Finland and Ireland. The Siberian tundra ablaze. Monstrous U.S. wildfires, along with record drought across the U.S. West and parts of Brazil …

Scientists had long predicted such extremes were likely. But many are surprised by so many happening so fast – with the global atmosphere 1.2 degrees Celsius warmer than the preindustrial average. The Paris Agreement on climate change calls for keeping warming to within 1.5 degrees.

"It's not so much that climate change itself is proceeding faster than expected -- the warming is right in line with model predictions from decades ago," said climate scientist Michael Mann of Pennsylvania State University. "Rather, it's the fact that some of the impacts are greater than scientists predicted."

That suggests that climate modeling may have been underestimating the "the potential for the dramatic rise in persistent weather extremes," Mann said.

Or look at this Grist Q&A with Daniel Swan of UCLA, also in July 2021:

Q: So this is what climate models said would happen?

A: There are some aspects of this where I do think that climate models have not fully captured everything that’s going on. There is evidence that, while climate models have done a very good job overall, when it comes to regionally specific changes or certain kinds of extreme events, that they don’t necessarily have a great handle on these events.

But where I differ with some other folks is that the models aren’t really designed to capture those things very well necessarily. Global climate models are designed and intended to simulate global climate. And in doing that, they do a really good job. They aren’t really tools that were expected to be really good at simulating regional-scale climate extremes. We know that they fail sometimes when they’re asked to do that somewhat out-of-scope task.

So when we get these really extreme events, like the unbelievable heat wave in the Pacific Northwest and these really extreme over-the-top flood events in Western Europe recently — these sorts of things that are beyond extreme relative to what we’ve seen historically — it probably shouldn’t be tremendously surprising that climate models don’t do a good job capturing them. Because the underlying physical processes are evolving on temporal and spatial scales that are finer than these models are intended to represent.

So we’re painting a picture where two things are true:

Climate scientists got the average temperature increases right, and the climate community has done a good job communicating them.

But we humans don’t notice averages, we notice extremes. Climate scientists also got some of the extremes right, but not all of them everywhere, and in any case they’ve been communicated less well.

Stay tuned, I think we’re going to see a lot more of these. The UN just dropped a big report on “Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability“ today that apparently charts 127 known climate degradation paths. I wonder how many more there really are?

Adapting the food system

When I hear people talk about climate disasters to come, one thing I hear about is the collapse of food systems. For example, climate change could cause soil degradation, or drought, or increasingly frequent crop diseases. Those could cause shortages, or panics, or outright famines. We have some idea of how bad these can get: humans have caused a few food system collapses over the years and they aren’t pretty.

I’m of a couple minds about this. On the one hand, yes, the food system seems likely to suffer shocks in a changing climate. But on the other hand, what can the average farmer do about it? I don’t mean to throw up my hands, I really mean to ask: if you know that you’re entering a phase of productivity decline due to climate change, what would you, as a farmer, do differently?

Maybe you’d seek out more resilient crop varieties; drought- and salt-tolerant crops are coming, but they’re likely to be expensive for a while as they come down the cost curve. Maybe you’d try to cut costs faster than you expect revenues to decline, but most farming today is pretty a low-margin, cost-optimized business. Maybe you’d try things like partial shading, agroforestry, or agrivoltaics, but putting new equipment on your farm could be a big operational risk. If you accept that risk, then you’d need to figure out how to finance it on your thin margins. Maybe you’d try to switch to regenerative farming practices, but it typically takes several years to be paid a premium for regenerative practices – a similarly big operational and financial risk. Maybe you’d contemplate converting to indoor farming, but if you’re growing commodities like corn and soy, it’s hard to see the economics penciling out.1 Maybe you’d pick an opportune moment and try to sell the farm, but who would buy? Presumably a buyer would have the same information as you?

If you’re a government, what would you do differently? Other than, you know, stop climate change? Maybe you’d subsidize farmers to ease the pain? In the US, we already do to the tune of tens of billions of dollars per year, but I have to think you’ll eventually hit some practical limit. Maybe you’d start relocation programs to encourage southern farmers to move north? Maybe you’d invade Ukraine?

Here’s an idea: maybe you’d treat the food system more like a variable energy resource, like solar or wind energy. An argument I like to make is that food is a carbon-based fuel. In past decades, production of this fuel has been more or less steady and predictable – let’s call it “baseload.” In light of climate change, food production may come and go in a less predictable way – now a “variable” resource. Recognizing this, maybe you’d intentionally build in some storage capacity so that you have excess when you need it.2 I was going to coin the term “food battery,” but let’s let that one lie.

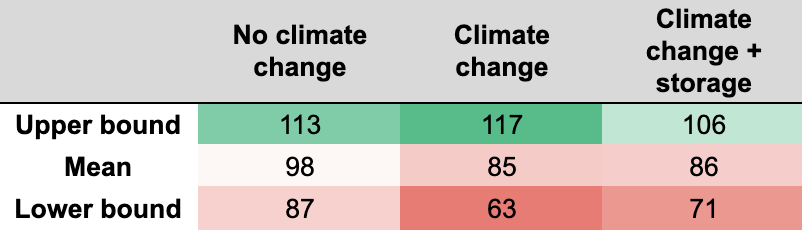

Could storing food help offset variability to a meaningful degree? Let’s put together a basic, oversimplified model, and assume the following:

In a “no climate change” scenario, food production = 100 ± 15, chosen at random.

In a “climate change” scenario, you have 10% lower production across the board, but 20% greater variability.

In a “climate change + storage” scenario, you have the same factors as above, but you also put away 20% of each year’s crop for next year. For now, assume this happens magically with no spoilage or loss of value.

Here’s what production could look like over a 10-year span:

Here are averages and ranges for each scenario:

After staring at this all for a while, I come away with four conclusions:

Climate change is bad. The averages are low, and the lows are lower. Okay, fine, I told the model to say that.

Increased variability isn’t all bad. Year 4 was great, and climate change helped! Okay, I told the model to say that too, but we do see analogous things like record cold temperatures in the real world.

Food storage blunts the effect of catastrophe in any one year. Look at years 5 and 9: in the “climate change” scenario, production is down more than 30%. Those are catastrophic numbers. But in the “climate change + storage” scenario, you draw upon 20% of the previous year’s excellent crop, netting out at only a 20-25% loss. The same is true in the opposite direction; look at years 3-4, 7-8, and 9-10.

If you have two or more bad years in a row, you’re still in trouble. Look at years 5-7.

And this is all in an idealized case for a made-up monolith I’ve been calling “food production.” Once you start layering on some real world inconveniences, it looks even more challenging:

Not all crops will behave the same way in response to climate change;

Some crops spoil with storage;

Even well-preserved foods lose value with storage;

Preservation and storage aren’t free;

It’s a lot to ask a farmer to put away 20% of their crop (see: margins);

Climate change isn’t steady-state; it’s not even linear.

There’s a lot more we could get into, but here’s the next place this all leads me: It seems unlikely that a more resilient food system that emphasizes storage is going to emerge on its own. Even if storage were free, spoilage weren’t a thing, and preserved food were as valuable as fresh food, then you’d have to contend with the time value of money. If you sold all your food today, then you’d have the money and could do with it what you wish. Maybe you’d put it to work improving the farm, or maybe invest it in an S&P 500 index fund and get an 8% long-term return. If you’re going to forego that cash today and store your food for a year, it needs to be worth it. Food prices do vary year by year, but outside of fine wines, you’re probably not making 8% per year by keeping it in storage.

Who might pay you to keep it in storage? Well, governments, for one. Regulators could incentivize long-term food storage in a number of ways – offering tax credits, paying for it in advance, or even just buying and storing it themselves. If we want stable food supplies in an age of increasingly uncertain agricultural production, we’ll probably have to pay for it.

In the US, we’ve done this in the past. Here are two examples:

Government cheese is a commodity cheese that was controlled by the US federal government from World War II to the early 1980s. Government cheese was created to maintain the price of dairy when dairy industry subsidies artificially increased the supply of milk and created a surplus of milk that was then converted into cheese, butter, or powdered milk. The cheese, along with the butter and dehydrated milk powder, was stored in over 150 warehouses across 35 states.

2) Combat rations (per Anastasia Marx de Salcedo’s Combat-Ready Kitchen):

Warriors in the field may be there for days on end, their souped-up metabolisms burning up to 4,200 calories over twenty-four hours, but the brutal business of kill or be killed hardly lends itself to sit-down meals. Enter the Natick [Soldier Research, Development and Engineering] Center. Their contribution to the army’s feeding strategy is reserved for a single occasion: combat. The graze-’n’-raze product line includes the Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE); First Strike Ration; Unitized Group Ration (UGR); Meal, Cold Weather, and Food Packet, Long Range Patrol; and the Modular Operational Ration Enhancement (MORE). Each has been laboriously engineered and manufactured on American soil to deliver an optimal nutritional payload to soldiers half a world and several years away. …

“Our shelf life is three years at eighty degrees because combat rations are a war-stopper and protected by Congress … When you talk to food technologists in the commercial sector, they’ll ask us what our shelf life is and we’ll tell them and they’ll be in shock.”

Relatedly, MREs have gained a cult following in recent years. Here’s the NYT trend piece to prove it.

So while we have some precedent around government support for storage and preservation technology, we shouldn’t get complacent. No matter how you look at it, the food system is likely to be in a pinch sooner or later, and we’ll need to be ready. Millions of lives are on the line. Here are a few of my priorities:

Enable better, longer-term food storage: Fresh bell peppers that last a year, not a week. The more of a food’s nutritional value we can preserve for longer, the more resilient the food system will be. Companies like MORI and Apeel Sciences are a great start, but can we go even bigger and with ideas like suspended animation?

Enable agriculture across climates: This has two prongs. We should develop drought-, salt-, and disease-resistant crop genetics to enable production to remain at current levels and in current locations. We should also develop novel crop genetics and farming technologies to enable production in new areas where the climate will soon be hospitable. If we get good at these, then we won’t need to store away as much food when times are good.

Zooming out: as long as humans exist, we’ll need to eat. As the food system becomes more variable, we’ll need to ensure that supplies are steady. We could learn a thing or two from the grid and the military.

Weaponizing the weather

Back in the first issue of this newsletter, we talked about how governments in certain parts of the world might soon respond to climate change by launching weather modifying campaigns. We talked about how the UAE has started doing these – they call them “rain enhancement projects.” Quietly, these have become a routine part of life; the government sees an opportunity to shock some extra rain out of the clouds, they fire up their drone-mounted lasers, it rains, and then they post about it on Instagram.

We also talked about some of the potential unintended negative consequences of these campaigns. Among many other possibilities, you could imagine the following:

Third, if I’m the government, I’d try to fire just enough drone-lasers to generate a manageable amount of rain only when I want it. But weather systems are sensitive and non-linear. Say the drones fire their lasers over here and nothing happens, so you have them fire over there. Suddenly it works too well and oops, we washed some cars into the sea. Or say someone at laser drone HQ misplaces a decimal and whoops, we flooded the financial district. This stuff seems hard to get right.

But what if you wanted to intentionally create negative consequences? What if you wanted to weaponize the weather? Throughout history, weather has played an important role in warfare. As far back as World War I,3 people have hypothesized that warfare can affect the weather. An Atlantic article from 1916 asked, “has the bombarding not only caused clouds but forced the clouds to send down rain?“ We know that weather affects warfare, we think that warfare can affect weather, and we know how to influence the weather in a crude way. So it seems very possible to turn the weather itself into a weapon? [Note: I don’t recommend this!]

It turns out people have been thinking about this for a while. Per The Guardian in 2015:

Weaponising the weather is nothing new. UK government documents showed that, 99 years ago, one of six trials at the experimental military station of Orford Ness in Suffolk sought to produce artificial clouds, which, it was hoped would bamboozle German flying machines during the first world war.

Like so many military experiments, these trials failed but cloud seeding became a reality in 1967/8 when the US’s Operation Popeye increased rainfall by an estimated 30% over parts of Vietnam in an attempt to reduce the movement of soldiers and resources into South Vietnam.

In recent years, the US military’s HAARP research programme has sown a blizzard of theories about how this secretive Alaskan facility has manipulated weather patterns with its investigation of the ionosphere. If HAARP really was so successful, it would probably not be closing this year.

Would the weather be an effective weapon? I’m no military tactician, but a few constraints come to mind:

If you want to modify the enemy’s weather and not your own, you’d probably want to have a significant physical presence upwind of the enemy, so that the weather goes away from you and toward them.

If you want to modify the weather in the same way for both you and your enemy, you’d presumably want to do it in a way that advantages you. Maybe you’d cause flooding for everyone in an area, hoping that the floods wash out an invading enemy’s camps while your buildings remain standing.

If you want to modify the weather in opposite directions for you and your enemy, then I guess you could get creative about positioning? For example, maybe you’d “steal” rain from the enemy before the moisture leaves your country and crosses into theirs.

In any case, you’d probably want to have a good understanding of weather modification, because the atmosphere is complex and nonlinear. We have a hard enough time predicting unmodified weather.4

If you figure out all these things, the effects will still probably be diffuse. Clouds are measured in kilometers, not meters.

Okay, so the US weaponized the weather during the Vietnam War, got found out, and now it’s considered a war crime. Even if you tried to revive the practice, it would seem to be a blunt, hard-to-control weapon. It begs the question: is there anything to worry about today?

Well, India seems to be at least a little worried. Per CNN in 2020:

In the next five years, the total area [in China] covered by artificial rain or snowfall will reach 5.5 million sq km, while over 580,000 sq km (224,000 sq miles) will be covered by hail suppression technologies. The statement added that the program will help with disaster relief, agricultural production, emergency responses to forest and grassland fires, and dealing with unusually high temperatures or droughts. …

And while other countries have also invested in cloud seeding, including the US, China’s enthusiasm for the technology has created some alarm, particularly in neighboring India, where agriculture is heavily dependent on the monsoon, which has already been disrupted and become less predictable as a result of climate change.

India and China recently faced off along their shared – and hotly disputed – border in the Himalayas, with the two sides engaging in their bloodiest clash in decades earlier this year. For years, some in India have speculated that weather modification could potentially give China the edge in a future conflict, given the importance of conditions to any troop movements in the inhospitable mountain region.

Though the primary focus of Beijing’s weather modification appears to be domestic, experts have warned there is the potential for impact beyond the country’s borders.

In a paper last year, researchers at National Taiwan University said that the “lack of proper coordination of weather modification activity (could) lead to charges of ‘rain stealing’ between neighboring regions,” both within China and with other countries. They also pointed to the lack of a “system of checks and balances to facilitate the implementation of potentially controversial projects.”

You can start to see how this gets tricky. There’s a plausible legitimate use of cloud seeding in the Himalayas, but it appears to be leading to negative outcomes for India. If you’re India, this is bad, intentional or not! Plus it’s scary: it shows that China could take more hostile actions if it wanted. You could see how India might assume the worst. But if you’re China, and other countries start giving you a hard time about scaring India, you could always fall back on the “we’re just trying to grow food and prevent drought!” defense. So while hostile weather modification is, again, a war crime, things seem to get murkier when it’s a natural resource issue. I guess we have our first geopolitical dispute of the geoengineering age.

Elsewhere

The first adaptation-focused private equity fund (article free with registration)

The carbon intensity of electricity really varies from place to place

Thanks for reading!

Please share your thoughts and let me know where I mess up! You can reply directly, leave a comment, or find me below:

They only pencil out for the most valuable crops out there. Because of this, it seems to me that betting on indoor farming for all our food is a bet on dramatic food price increases.

I know, I know, agriculture is already variable, and we already store food. For the purposes of this discussion, we’re talking about ramping up storage by a lot.

I’m sure there are reports going farther back than this.

Though we’ve gotten pretty good at forecasting! Michael Lewis’ The Fifth Risk covers this beautifully.

Love this analogy of food as an energy system. To take the analogy a bit further (too far?), what would the equivalents to firm power and overbuilt renewables look like? Any reason for any of these to be disproportionate in energy or food?