Note: The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Energy Impact Partners.

Geoengineering

As we talk about here from time to time, I believe that we will do a significant amount of geoengineering before all is said and done. My theory is:

Geoengineering is an idea that (1) starts at the fringe sounding too good to be true. Then (2) serious people get concerned about the hazards it presents, then (3) it gains some traction in those circles, and then (4) oh shit we really need this now, go go go! I think it’s at stage two or three in most places.

Since nations are the main actors capable of large-scale deployment, geoengineering will inherently be a national policy issue. The big issues in US politics tend to be put through partisan filters, and climate tech is no exception: we’ve seen this happen with fossil fuels, renewables, nuclear, and perhaps most relevant to geoengineering, with carbon capture, previously viewed as a backup option in case of failure to decarbonize. On top of that, geoengineering is a much more dramatic measure than the others we’ve contemplated. So I think it will also become partisan in time.

But it hasn’t yet, and it’s interesting to think about how the battle lines will shape up. Which party will take which side? Will there be a bipartisan consensus to ban it? A law quietly passed through Secret Congress?

Let’s do a thought experiment. Why might either party like or dislike geoengineering?

Why Democrats should like geoengineering:

It directly counteracts radiative forcing – the actual agent of climate change.

It’s fast (~weeks) compared to carbon management (~decades).

It buys time for those most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Why Democrats should dislike geoengineering:

It’s dangerous and could have unintended consequences.

It’s an unnatural intervention in the environment, which we’re trying to protect.

If we have this band-aid, we’ll be less motivated to solve the underlying problems.

Why Republicans should like geoengineering:

It directly counteracts radiative forcing without necessarily eliminating the oil and gas industry.

It’s much cheaper than managing carbon – billions versus trillions of dollars.

It’s a chance for the US to out-innovate other countries (i.e. China), and there are military implications to being out ahead.

Why Republicans should dislike geoengineering:

Government shouldn’t be involved in managing the climate.

Climate change isn’t as bad as those on the left think, so geoengineering is an overreaction.

It’s dangerous and could have unintended consequences.

Given these elements, it’s not obvious to me how things will shake out. So let’s try going in reverse. If you assume a certain partisan outcome, what would have led to it? How plausible does that sound?

For this, I asked ChatGPT to write articles about a geoengineering debate with different political alignments. Which sounds most likely to you?

Democrats for, Republicans against:

Republicans for, Democrats against:

Nuanced bipartisan consensus:

Republicans and Democrats quietly ink a deal:

A few interesting things pop out of this exercise. Pro-geoengineering Democrats like that it buys time for other solutions to start working. Pro-geoengineering Republicans latch on to it as a quick fix that would avoid the need for new regulations. Anti-geoengineering Democrats don’t like the unintended consequences and potential for moral hazard. Anti-geoengineering Republicans are also skeptical about unintended consequences and didn’t think it was a proven solution. ChatGPT wrote the bipartisan consensus piece about mirrors, but didn’t cover other more commonly discussed forms of geoengineering. And even ChatGPT doesn’t think geoengineering could get done quietly without lots of backlash. Maybe this is a silly exercise – ChatGPT famously gets lots of things wrong – but I found it helpful.

On balance, here’s what I think will happen. If a serious, large-scale geoengineering deployment proposal comes to Congress by 2030:

Geoengineering will become a hotly contested partisan issue as the prospect of widespread deployment becomes more and more real.

Republicans are more likely to support it than Democrats – mostly because the economics are hard to ignore, but also in part because Democrats are more likely to oppose it.

That being said, this will be a high-variance issue. What I mean by that is that several of the scenarios above seem pretty plausible all things considered. If you ran 100 simulations of party alignment on geoengineering, I don’t think any one of the four outcomes above would win more than half the time, but I do think the results would be polarized most of the time.

Given strong reactions and high variance, what could tip the scales one way or another is how geoengineering is introduced. For example, limited deployment by a poor country responding to a devastating heat wave could foster support on the left, but a “move fast and break things” approach could quickly mobilize opposition.

When this happens, let’s check back to see how this prediction fares.

Year-end roundup

It’s the end of the year, so let’s sit back, grab a hot drink, and check in on some takes!

The next climate tech hub

A year ago, I made some predictions about where the next climate tech hubs would emerge by 2030. Long story short, I’m most bullish on Denver, Seattle, and Houston. It’s a tricky thing to know when a city has “made it,” but I did mention some concrete things to watch for:

Tech talent to migrate to Denver

Entrepreneurial culture to evolve in Houston

Capital to flow into all three

So how are they doing?

Culture in Houston: trending positively.

Greentown Labs Houston has gone from zero to 76 members since opening in the spring of 2021.1 It's hard to overstate the impact of Greentown's first branch on the Boston ecosystem, so this is a welcome development.

Across the street, The Ion opened in 2021, with 266,000 square feet of space and a regular stream of founder-oriented events.

Talent in Denver: unclear.

According to CBRE’s 2022 Scoring Tech Talent report, Denver climbed from #12 to #10 in the nation over the past year.

Denver is also “the third-most concentrated market for millennials at 24.1% of its population.”

However, migration appears to be dominated by software talent, and there isn’t much evidence to suggest that climate tech is benefiting in particular.

Capital: trending positively.

In a year where VC investment pulled back relative to 2021 highs, Houston, Denver, and Seattle held constant or increased as a percent of total investment.2 This is good news!

On top of that, five of Seattle’s 10 largest VC rounds in 2022 were in climate tech, and Houston’s five largest VC rounds in 2022 were all in climate tech.

I couldn’t find such a list for Denver, but the year included highlights like Jetti Resources’ $100MM Series D, Meati Foods’ $150MM Series C, AMP Robotics’ $91MM Series C, EIP portfolio company Project Canary’s $111MM Series B, and Electra’s $85MM unstealthing event. Those five account for >$0.5B alone.

Against a backdrop where a quarter of all venture dollars now go into climate tech, over-indexing in these cities is a good sign.

Verdict: Early signs look good.

Heat

In January, I wrote about outdoor labor in a warming climate. It’s a tough one; there’s going to be more extreme heat in more places, but a lot of labor just needs to happen outdoors. I came away with two thoughts about how you might deal with this:

Providing cooling to outdoor workers, such as cooling tents or air-conditioned construction equipment

Limiting outdoor work in excessive heat, through measures such as increased break time or work stoppage during heat waves

Over the year, a few blue states like California and Washington adopted measures to protect workers, while a handful of other states either hotly debated or rejected them.

Verdict: The conclusion from the original piece – “it seems like outdoor laborers are going to lose” – is unfortunately looking good.

How’d wildfire season go?

In June, I took a look at how the US wildfire season was going. It didn’t look good. But there was lots of dry season left. How’d the rest of the year go? In a word, quietly. Why? We got lucky.

When a string of wildfires broke out in California this spring, experts saw it as an unsettling preview of another destructive fire season to come — the consequence of forests and grasslands parched by persistent drought and higher temperatures fueled by climate change.

Yet, by the year’s end, California had managed to avoid widespread catastrophe. Wildfires have burned about 362,000 acres this year, compared with 2.5 million acres last year and a historic 4.3 million acres in 2020.

“It’s really just that we got lucky,” said Lenya Quinn-Davidson, a fire advisor for the University of California Cooperative Extension.

This year’s relatively mild wildfire season doesn’t mean that the landscape was much less vulnerable, that the forests were in better condition or that climate change had less of an effect on the intensity and behavior of wildfires than in previous years, Ms. Quinn-Davidson said. Instead, a combination of well-timed precipitation and favorable wind conditions seemed to play the biggest role.

Verdict: Wrong, but happy about it!

Snowboard bans

Also in June, I linked to an article about a federal court ruling that Alta, Deer Valley, and Mad River Glen – three ski resorts famous for banning snowboarding from their slopes – must allow snowboarding immediately. “Justice for SLC snowboarders,” I wrote. Well, a few months later I started looking at ski trips and thought I’d check the ruling again before booking. I came back to that article, and you know what I found? An April 1 publication date.

Verdict: Ate the onion!

Crypto

In July, I wrote about crypto’s energy footprint and what the debate said about our values. My point of view was:

So I guess here’s where I land: it seems like crypto uses a whole lot of energy compared to a system that mostly works for most people most of the time. I like that we have another option in crypto, don’t like the level of energy use and grift, and fear that we may throw out the baby with the bathwater.

The news since then has been twofold:3

FTX collapsed spectacularly in November, leading to a widespread crypto crash. Along with it came a much lower Bitcoin energy footprint. Bitcoin is now only the equivalent of Colombia, not Argentina.

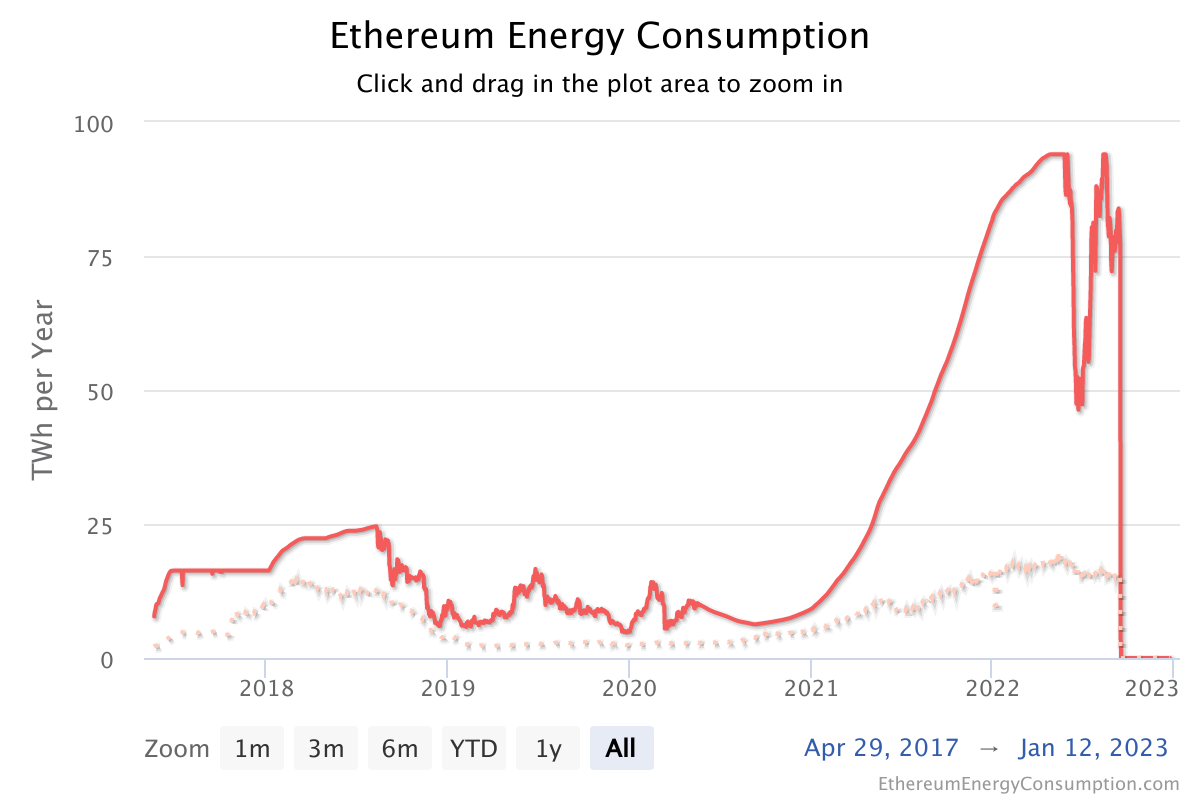

Ethereum successfully converted to proof-of-stake and cut its energy consumption by ~99.95% without compromising the integrity of its blockchain. This was widely hailed as a success for the crypto community.

Verdict: Bathwater’s gone; now was there a baby in there?

Thanks for reading and happy new year! Lost more to come in 2023, including a deep dive I had to cut for space this time around.

Elsewhere:

Thanks for reading!

Please share your thoughts and let me know where I mess up:

These 2022 projections are rough for a few reasons: 1) Q4 2022 data aren’t out yet, so I made 2022 projections by annualizing data available through Q3. 2) The report doesn’t track Houston, but it does track Texas and the Austin-Round Rock metro area. To estimate VC investment into Houston, I subtracted Austin-Round Rock from Houston, then divided by two (assuming some VC investment goes to Dallas, San Antonio, and the rest of Texas). 3) Q3 data weren’t available for Austin-Round Rock, so those data come from Q2.

Note: The first crypto crash of the year happened before the June post.