Note: The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Energy Impact Partners.

People don’t like new flood maps

Water is one of the harder parts of climate change. Because of changing weather patterns, sometimes you don’t have enough water where you want it, and sometimes you have too much water where you don’t want it. Flooding falls in this second bucket. The risk of flooding looms larger in more places than it used to.

What should you do about flooding? Here’s my order of operations:

Prevent or contain flooding — for example, by building levees and diversion channels, raising land, or, you know, stopping climate change.

If you can’t do that, then prevent floods from damaging things that matter — for example, by building more porous infrastructure or putting houses on stilts.

If you can’t do that, then use flood insurance to at least price the risk and compensate for losses.

Option three is obviously a last resort. And yet, it’s where we’re innovating fastest. The first wave of climate adaptation startups has featured quite a few efforts around flood insurance. My read is that this is the lowest hanging fruit since it doesn’t require building physical infrastructure. It’s faster to build a new insurance model than a levee. (If you know how to build levees really quickly, you should send me an email.)

One result of starting with better insurance is that flood risk gets repriced before property owners get better physical tools to deal with flooding. This means that some combination of the following will happen:

Premiums will go up for the same coverage,

Premiums will stay the same but coverage will get worse, or

Insurers will exit markets where they can no longer price risk:

Confidently, or

At levels that the market (policyholders, governments) will accept.

In all of these scenarios, home values are also likely to decrease as word gets around that there’s all this “new” flood risk.

In a macro sense, this is good. Insurance is critical to modern society, and it doesn’t work without reasonably accurate pricing of risk. But at the same time, when you give insurers a reason to think risk has gone up, you’re not going to make a lot of friends. The thing about correcting an underpriced risk environment is that people hate when you do it.

So unsurprisingly, when Quebec proposed some new flood maps, it made people unhappy.

Opposition is growing over Quebec's new flood maps, with the province's professional association of real estate brokers warning they could disrupt the housing market and directly impact homeowners.

Rene Leblanc, who has invested in his home on des Macons Street in Pierrefonds for 40 years, said the new maps put his future in jeopardy.

“I always thought that one day the value of that home would supply me with the necessary funds to go into that last chapter of my life. And now I find that may not happen,” Leblanc said in a recent interview.

Macons Street flooded only once, in 2017, but it's considered high risk according to flood maps from Montreal’s metropolitan community.

“The new proposed flood map caught us by surprise. Actually, surprise doesn't do it justice. We were shocked by it,” Leblanc added.

Christian Andrew Marco, another Pierrefonds resident, shared Leblanc’s concerns.

“Everything is a concern now because now we're in a red zone,” Marco said.

Nathalie Bégin, chair of the QPAREB's Brokerage Practice Committee, said homeowners living in flood zone are facing many questions about their property values.

“For those who are really on the map in the risky zone, there is going to be a big impact,” she said.

Bégin noted revised flood maps will lead to a significant decline in the value of even more properties.

The proposed maps put around 77,000 properties in flood zones compared to around 22,000 before meaning that many more homeowners will have difficulties selling.

“Even if the property doesn't have a recurrence flood risk, just being marked on the map will cause problems,” Bégin said.

The association participated in a public consultation on the flood zones and recommended that the government introduce financial assistance programs and communicate the changes with people who are affected.

“It will be a good tool to go to the insurance company and the lenders to make a decision, a clear decision, if they're going to give a mortgage or not or give insurance or not,” she said.

In a statement, Quebec’s Environment Ministry said public consultations are over and official flood maps will be published once approved by the government, though no release date has been set.

Surprise! You used to have desirable waterfront property, but now you live in a danger zone. This article captures all the predictable dynamics: outrage at the effect on property values, praise from insurers and lenders, people questioning the validity of the map, weak attempts by the government to soften the blow or delay release of the final map.

Expect more of this. Similar things have started happening as Zillow and other listing sites have rolled out flood risk assessment in its listings. And anecdotally, when my wife and I were buying a house, we filtered pretty hard for flood risk.

I feel for the homeowners who thought they were buying one thing, only to find out years later that their most valuable asset is much less valuable for reasons outside their control. It would be better if fewer people’s net worths were tied up in their homes. But I don’t control the housing market. People are going to pay less for your house if they think it’ll flood. Floods are bad!

For the last few decades, a huge housing deficit in North America and a somewhat oddly regulated residential real estate market create a low-information environment favorable to sellers. Buyers have to waive all sorts of protections that would typically be afforded to people making the largest financial decision of their lives. For example, try (as we did) making an offer on an old New England house that is contingent on an inspection for lead paint. You’ll be laughed out of the room. There’s lead everywhere, but nobody wants to deal with the liability, and sellers can set the terms. Don’t ask, don’t tell, buddy! So as technology like flood modeling injects new information into the real estate market, buyers are getting a little more power and sellers are getting a little more to worry about. Prepare for more of this as modelers get smarter about fire, wind, heat, and other risks.

One way to view climate change is as a structural shift in the risk environment. We either have to mitigate the risks or someone is going to figure out how to price them.

Hydrocarbons vs. hurricanes

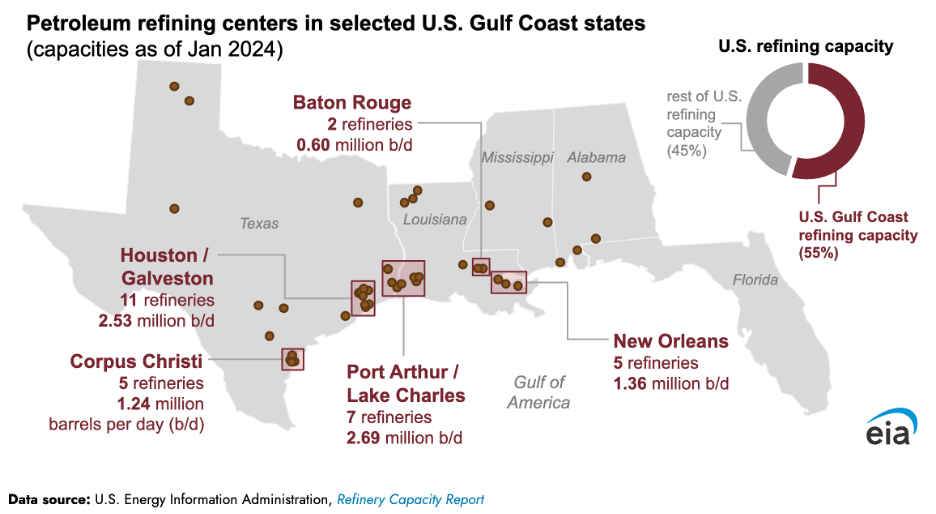

Between oil and natural gas, the US produces about 32 million barrels of oil equivalent per day, and those hydrocarbons constitute about 70% of US energy. About half of that energy has to pass through refineries along the Gulf Coast. But as hurricanes become more frequent and intense, the Gulf Coast is increasingly exposed to weather damage. Is that a problem for about 35% of US energy?

The US Energy Information Administration tracks this sort of thing. They find that producers take capacity offline when either it’s too dangerous to send workers to work, or when facilities have been damaged. They observed that for a few stretches last year, as much as 50% of oil and 40% of gas refinery capacity were taken offline.

What happens to the hydrocarbon system when you take refineries offline? Consumers still need energy, and the fuels need to go somewhere. Fortunately there are roughly six things that start happening all at once:

Rerouting: We have refineries elsewhere in the country, and we have access to them via ports and pipelines. Maybe some of them have some spare capacity to take in more crude. You can reroute tankers and pipeline flows toward the refineries where there’s capacity.

Onshore storage: Crude storage is cheap – you can just put it in a tank. In Cushing, OK alone, there’s enough tank space for 91mm barrels of oil (about 7 days of US oil use). Gas storage is a bit more expensive, but we have huge subterranean caverns built for this purpose.

Tanker queueing: Tankers hang out offshore for a few days until there’s enough slack in the system for them to unload.

Well shut-ins: If you own an oil well and there’s nowhere for your oil to go, the price of crude drops and it starts to make sense to shut your wells in. It’ll still be there in a few days when the price rebounds.

Ramping up other supplies: The other half of US oil and gas come from places that don’t flow through Gulf Coast refineries. You can lean a little harder on them for a few days.

Demand response: While crude prices have dropped because refinery capacity is the choke point, refined fuel prices have gone up for the same reason. Price-sensitive consumers of refined fuels make do with a little less energy. Supply and demand in action.

So, despite how much oil and gas flow through the Gulf Coast, hurricanes aren’t actually that much of a problem today. We have options.

Part of the hydrocarbon system’s stickiness is its resilience. There are all kinds of levers that make sure it works under all kinds of conditions! Russian gas suddenly cut off? Import more LNG from the US. Winter fuel demand higher than expected? Draw down on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve for a few weeks.

I spend my days thinking about decarbonization. Much of that effort flows through the electrical grid. As more variable renewables come online, weather events become more severe, and demand grows, we’re going to be asking more of a more stressed grid. That means we will need resilience built in, and we will need to pay for it. If this is the direction we want to go, I can’t emphasize strongly enough how it just has to work. People hate things that don’t work! They will seek out systems that do work!

And so it matters that here in decarbonization world, we don’t have all six options that the hydrocarbon system has. We have maybe two and a half? Grid resilience today means things like demand response to reduce the severity of peak events, batteries to store a few hours of electricity, and microgrids to provide local redundancy. When that same hurricane takes out a section of the grid, it’s harder for the system to adapt. It doesn’t have the same options that the hydrocarbon system has.

At core, I think this is because electricity is a just-in-time product whereas hydrocarbons aren’t. You can shut in a well and extract the oil tomorrow. You can’t do the same with a wind turbine; that wind is gone forever. You can put oil in a tank so cheaply that it basically doesn’t matter. Not so for electrons; you need expensive electrochemical tanks called batteries to store them.

Conventional energy world has already answered most of the hard questions about resilience. Clean energy world is still working through them.

What’s new in geoengineering?

I thought we were supposed to be the cowboys here in the US? From The Guardian:

Real-world geoengineering experiments spanning the globe from the Arctic to the Great Barrier Reef are being funded by the UK government. They will test sun-reflecting particles in the stratosphere, brightening reflective clouds using sprays of seawater and pumping water on to sea ice to thicken it.

Getting this “critical missing scientific data” is vital with the Earth nearing several catastrophic climate tipping points, said the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (Aria), the government agency backing the plan. If demonstrated to be safe, geoengineering could temporarily cool the planet and give more time to tackle the root cause of the climate crisis: the burning of fossil fuels.

The experiments will be small-scale and rigorously assessed before going ahead, Aria said. Other projects in the £56.8m programme will model the impacts of geoengineering on the climate and research how it could be governed internationally.

Geoengineering is controversial, with some scientists calling it a “dangerous distraction” from cutting emissions and concerned about unintended climate impacts. Some previously planned outdoor experiments have been cancelled after strong opposition.

However, given the failure of the world to stop emissions rising to date, and the recent run of record hot years, backers of solar geoengineering say researching the technology is vital in case an emergency brake is needed. The Aria programme, along with another £10m project, makes the UK one of the biggest funders of geoengineering research in the world.

ARIA is the UK’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency, which is sort of a UK version of DARPA, but aimed at boosting the economy rather than the military. True to ARPA-style program design, the projects cover a wide range of approaches, everything from strategically placing dust in the right parts of the stratosphere to adjusting the charges in clouds. For example, there’s a £10mm project led by the University of Cambridge called “Re-Thickening Arctic Sea Ice”:

Researchers will conduct controlled, small-scale experiments in Canada across three winter seasons (2025-26 to 2027-28). The process involves pumping seawater from beneath existing ice and spreading it on top, where the frigid air freezes it quickly, creating thicker ice patches. Over the course of the project (and if the early experiments suggest the approach is ecologically sound), later experiments will aim to cover areas up to 1 km² per experiment site. The key questions are whether this thicker ice lasts longer into the summer, how it might affect ice movement, and what the local ecological impacts are. These experiments will be conducted in close collaboration with local communities and under ARIA's stringent governance framework, prioritising safety and environmental monitoring. The goal is to gather essential real-world data to rigorously assess if this intervention warrants further consideration.

These are interesting and I hope we learn whether or not any of them could work. If they could work technically, then they’ll earn a chance to work their way through the minefield of public perception that killed prior efforts like SCoPEx and the UW Marine Cloud Brightening program. The ARIA program lays out a detailed community engagement flowchart and governance and oversight committee designed to head off these risks, but I don’t know, it doesn’t seem like something you can committee your way through. At least they’re taking shots on goal.

In contrast, here in the US, a few states are banning geoengineering and cloud seeding:

A while ago, I ran a silly little thought experiment using ChatGPT to see which sounded more plausible: Democrats or Republicans supporting geoengineering? At the time, I came away predicting that Republicans would be more supportive. Turns out that was wrong! Red states are banning it first.

But my other prediction is faring better:

Given strong reactions and high variance, what could tip the scales one way or another is how geoengineering is introduced. For example, limited deployment by a poor country responding to a devastating heat wave could foster support on the left, but a “move fast and break things” approach could quickly mobilize opposition.

It’s just so easy to paint a scary picture. Articles about making sunsets aren’t helping. Let’s hope the Brits know what they’re doing.

Elsewhere:

Rainmaker announces Series A and preliminary data on cloud seeding

The American Enterprise Institute kind of likes geoengineering?

Thanks for reading!

Please share your thoughts and let me know where I mess up. You can find me on LinkedIn and X.