Forbidden steak

2. New meat dropped, the next climate tech hub, and health as climate adaptation

Note: The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Azolla Ventures or Prime Coalition.

Designer meat

A few years ago I used to work at ARPA-E, an innovation agency within the US Department of Energy. Strictly speaking, ARPA-E funds research projects: it takes in proposals on certain topics, reviews the proposals, decides which proposals to fund, and then helps manage the research projects. There are many other agencies that do similar things.

But one key difference is that the technical staff at ARPA-E, not Congress, choose what topics the agency will fund, so long as they fit within a broad mandate and don’t overlap too much with topics that are already being funded by another office. So the staff hunts for high-risk, impactful technology areas that other agencies aren’t authorized to fund, or that investors aren’t yet ready for. Another key difference is that the technical staff are swapped out every 3-5 years,1 so there’s a culture of thesis development happening in many fields at once. Everybody’s working on something new.

While I was there, one thing I got excited about was cultured meat. My rough pitch was (video, deck):

Meat demand goes up with GDP per capita.

GDP per capita is going up around the world.

Raising livestock requires lots of land (~70% of all agricultural land), wastes lots of energy (beef is ~2% efficient), and produces lots of greenhouse gases (~1/6 of global emissions).

While wasting energy isn’t great and GHG emissions are definitely bad, land is the real limiting factor: there isn’t enough usable land on planet Earth to meet the demand we expect in 2050. Meat-making technology must improve.2

Smart people like Pat Brown thought of this long before me and invented plant-based meats. These are fantastic products, but they will not capture more than ~10% of the meat-eating public and therefore about 9% of meat-related emissions. This is because:

They’re novel consumer products, and novelty has the bad habit of wearing off (Note: I’m starting to think I was wrong on this one).

They taste almost as good as the real thing, but not better. There’ll always be a real, better-tasting burger next to it on the menu.

Fundamentally, they’re an imitation. They have to pass the “Turing test” to gain wide acceptance. This is hard – humans have evolved pretty good BS detectors to avoid eating poisons.

Solution: grow real meat in cell culture and engineer it to be a far superior product to animal-derived meat. In order to decarbonize the meat industry,3 the world needs to crave it.

What does such a product look and taste like? I think probably like nothing we know today.4 My analogy is the Cheeto: ruthlessly engineered for deliciousness and stickiness, looks nothing like the lowly potato chip, never goes bad, is definitely not healthy. I didn’t know it was made from corn for a solid few decades; it didn’t matter. It’s a genius, alien product that has entered the mainstream and stood the test of time. I want the Cheeto of cultured meat.

As far as I could tell, nobody was pursuing this. It’s been about three years since I first started working on this and that still seems true, despite massive VC investment and the development of cultured meat startups like UPSIDE Foods (fka Memphis Meats), Mosa Meat, and others. The strategy is still imitation: burgers, steaks, sliced chicken, and so on.

So, while I don’t follow cultured meat as closely as I used to, I still keep an eye out for technologies that could fit the old thesis. Here’s one I didn't see coming: “Ouroboros Steak grow-your-own human meat kit is ‘technically’ not cannibalism.”

A group of American scientists and designers have developed a concept for a grow-your-own steak kit using human cells and blood to question the ethics of the cultured meat industry.

Ouroboros Steak could be grown by the diner at home using their own cells, which are harvested from the inside of their cheek and fed serum derived from expired, donated blood.

The resulting bite-sized pieces of meat, currently on display as prototypes at the Beazley Designs of the Year exhibition, are created entirely without causing harm to animals. The creators argued this cannot be said about the growing selection of cultured meat made from animal cells.

If you’re wondering, there are indeed photos of the exhibition.

I mean, I guess it was a matter of time until someone did this? I have to admit that while the thought of cultured human meat did cross my mind, I didn’t think someone would go all the way and bring it into the world. To be fair, the researchers also say:

"We are not promoting 'eating ourselves' as a realistic solution that will fix humans' protein needs. We rather ask a question: what would be the sacrifices we need to make to be able to keep consuming meat at the pace that we are? In the future, who will be able to afford animal meat and who may have no other option than culturing meat from themselves?"

I have some thoughts:

This technology seems designed for exactly this headline. I assume the researchers had noble intentions, but you had to know this would become clickbait if it took off, right?

I’m always on the lookout for good names, and Ouroboros is a good name.

The description does seem to present a way around one of the stickier problems in cultured meat, which is the need for fetal bovine serum. However, I’m not sure this is linked to the human meat element in an inherent way. Presumably you could do the same thing by drawing blood from a cow without killing it? I assume I’m wrong here, let me know if so.

Would I eat it? I guess maybe? I’d like to say I’d be up for it, but I could also imagine that if I actually put fork to lips, some ancient evolutionary machinery might kick into gear yelling “DEAR LORD DO NOT DO THIS” and I’d have no choice but to obey.

Last, the researchers’ quote almost sounds like a threat? Fix our broken food system or the bottom 99% will be reduced to culturing and eating our own meat. While I think industrialized cultured meat could work, this at-home dystopia doesn’t strike me as remotely realistic form of climate adaptation. I look forward to re-reading this newsletter in 2050 as I reheat yesterday’s harvest of thigh tissue.

The Ouroboros story does raise a different, important question: if you had the tools to invent and scale up any meat, what would you create? For me, it wouldn’t be chicken. I have a few pet ideas, but I’m not creative or expert enough to go very far with them. I’d think I’d want some subset of:

Novel taste/texture

Known but hard-to-access taste/texture (e.g. Orbillion Bio and I guess Ouroboros?)

Optimized nutritional profile

Reduced spoilage

Novel form

Radically reduced cost vs. animal-derived meat

Scalability with conventional equipment

Strong branding (e.g. Nuggs)

I’m sure there are some things missing, and I’d love to hear from you if you’re working on them. Decarbonizing meat while increasing production is an exceptional challenge – one of the hardest in all of climate. Many great minds in biotech are working on it already; I’m hopeful we’ll start going bigger and badder than imitation soon.

The next climate tech hub

My teammates and I at Azolla Ventures think about diversity a fair bit. Diversity comes in many forms – race, ethnicity, and gender being top of mind – but another important form of diversity is geography. In the US, venture investment is famously concentrated in the San Francisco Bay Area, New York, and Boston, with most other cities part of a long exponential tail. In climate tech, it’s really just the Bay Area and Boston. I’m of two minds about this:

On the one hand, there are real, organic reasons that tech hubs crop up in some places and not others. To oversimplify things, in Silicon Valley these were Stanford and Berkeley, DoD-funded semiconductor R&D, good weather, and inexpensive space (if you can believe it). In the Massachusetts textile industry of the late 18th/early 19th century: hydropower, British textile IP, and risk capital. There’s also real, self-reinforcing value in tech hubs. In Silicon Valley, the emergence of venture capital followed early successes in the semiconductor industry. In my own experience in Boston, you build better relationships by going to events at Greentown Labs than you do by scheduling zoom after zoom. I’m far from the first person to write about this.

On the other hand, why on Earth would most new technology come from three cities? Definitionally, there are fantastic entrepreneurs in every major city – cities don’t thrive without successful businesses. Moreover, climate technologies are more likely to be hardware-based, making physical proximity to different industries in different places all the more important. While I don’t have any preconceived notions about what that long exponential tail of other cities should look like, it seems likely that some of them should be poised to break out.

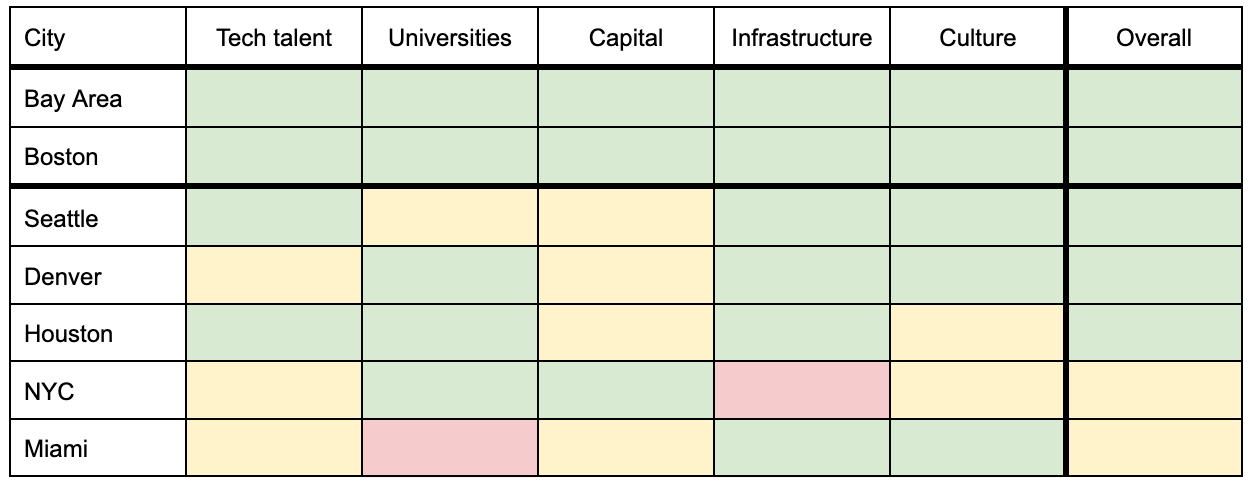

Prediction: Seattle, Denver, and/or Houston will join the Bay Area and Boston as the next major climate tech hub by 2030. More specifically, these cities will mint multiple climate tech unicorns, leading multiple climate tech VCs to open local offices. Each of the three has three of five key elements in place already:

(Source: Author)

To spell these out:

Tech talent: Concentration of people. Traditional “tech,” industries relevant to climate tech (e.g. manufacturing), incubators, accelerators, entrepreneur-friendly law firms, and so on. Because of time limitations, I’m judging mostly by experience.

Universities: Two or more major research universities with climate-relevant expertise and MBA programs.

Capital: Investment from angels, VCs, project financiers, government agencies, philanthropists, and so on. Ideally there’s a critical mass living in the city. As a proxy, I’ll draw from the Q3 2021 Pitchbook-NVCA Monitor and Pitchbook/Revolution’s Beyond Silicon Valley. I’ll also throw in some personal experience.

Infrastructure: Accessibility and affordability of office and lab space. I’ll pull from JLL’s most recent Office Outlook, Industrial Outlook, and Life Sciences Lab Outlook. I’m no real estate expert, so let me know if there are better indicators out there.

Culture: Squishier. Entrepreneurial vibe, proximity to industry, vulnerability to climate change, quality of life.

Notes and caveats: I’m keeping things simple and using a green/yellow/red rating system. If you’re looking for an objective ranking, this definitely isn’t it. For now, I’m restricting this analysis to the US. Frankly, I don’t know enough about cities outside the US to say much meaningful. I hope to some day.

—

Let’s start with the current climate tech hubs:

Bay Area

Tech talent: Highest concentration in the country. Activate Berkeley (fka Cyclotron Road) and Powerhouse are major organizing forces. Green.

Universities: Stanford and Berkeley. Green

Capital: Awash in capital. Bay Area startups received $62.1B in VC in 2020 and $88.4B through Q3 2021. Green.

Infrastructure: It’s there, but you’ll pay for it. SF is much more expensive than Silicon Valley or Oakland. Green.

Culture: People love to hate Bay Area culture, but it’s still the center of the technology industry. With wildfire smoke pouring in every summer, there’s an increasingly mainstream motivation to address climate change. Green.

Overall: Green.

Boston

Tech talent: Multiple generations of entrepreneurs in town. Greentown Labs is the convening force, and organizations like Activate Boston have added a ton of depth. Green.

Universities: MIT and Harvard, plus Tufts, Northeastern, BU, BC, Olin, and many others. Green.

Capital: High concentration of VC firms. Boston startups received $17.7B in VC in 2020 and $23.7B through Q3 2021. Green.

Infrastructure: Expensive in town; more reasonable along America's Technology Highway. Per JLL, Boston is off the charts as a life sciences hub, but industrial real estate is severely supply-constrained. Still green.

Culture: Strong, with a history of biotech and hardware innovations. The main climate threat is sea level rise, and people are noticing winters getting warmer. Green.

Overall: Green.

—

Let’s move on to the next generation:

Seattle

Tech talent: Anecdotally, great. We regularly see high-quality climate tech startups from Seattle and recently invested in one. There’s a budding fusion community. Talent pools at Amazon, Microsoft, Boeing, Blue Origin, and others. Green.

Universities: UW is fantastic for computer science, chemistry, and materials science, but it’s the only major research university in the area. Yellow.

Capital: Surprisingly for the home of Amazon and Microsoft, Seattle receives a fraction of the VC dollars that the tech hubs do. In 2020, this was $4.7B; through Q3 2021, it’s $5.1B. Anecdotally, not much of that goes to climate tech. Yellow.

Infrastructure: Office space is expensive, but industrial space is much more reasonable. Green.

Culture: Strong history of environmentalism, tech, and aerospace. But I’ll admit I don’t know Seattle well! Green.

Overall: Probably the closest to a climate tech hub outside of SF/Boston today. Green.

Denver

Tech talent: There are promising signs (e.g. DMC Biotechnology, many ARPA-E awardees, natural resource expertise), but I have to admit I don’t know enough to say something very concrete. Given the job I have, that’s not a great sign. Yellow.

Universities: The city’s sleeping giant. CU Boulder (high tech, materials), CSU (mechanical, agricultural), CO School of Mines (energy, natural resources), NREL (renewables). Green.

Capital: Seed- and early-stage VC activity will exceed $1B for the first time in 2021. Overall VC investment was $2.5B in 2020, $3.5B through Q3 2021. However, anecdotal experience suggests little of this goes to climate tech. Biggest area for growth. Yellow.

Infrastructure: Office space is cheaper than average; industrial space is more expensive than average; top-10 US city for biotech. Green.

Culture: Great combination of science, industry, environmentalism, and quality of life. Green.

Overall: I’m excited about Denver. Most of the pieces are there. Green.

Houston

Tech talent: Incredible pool of engineering, business, and supporting talent in the oil and gas industry. The transition toward climate is starting, best exemplified by Greentown Houston opening in 2020. Green.

Universities: Rice and University of Houston, plus established pipelines from UT, A&M, and others. Green.

Capital: I don’t have direct data, but: in 2020, TX startups received $4.8B in VC; $2.3B went to Austin. Through Q3 2021, TX startups received $6.5B in VC; $3.8B went to Austin. Let’s assume most of the remaining $2.5-2.8B were split between Houston and Dallas, so we’re in the $1-2B/year range for Houston. Not a lot relative to other cities on this list. However, there’s huge potential: oil and gas investors representing billions of dollars who are increasingly turning their attention toward climate. Overall, yellow.

Infrastructure: Space is cheap and plentiful relative to other cities. Green.

Culture: Oil and gas still dominates, but there’s a growing energy transition movement that I wouldn’t ignore. Paired with the fact that Houston is at the front line of climate change (hurricanes, heat waves, and freezes in the last five years), I think this will pick up. Green.

Overall: Let’s get petroleum engineers working on geothermal and carbon sequestration. Green.

NYC

Tech talent: Great for software and biotech, less great for hardware. State-level efforts have mostly been focused upstate. Yellow.

Universities: Columbia and NYU – not known as entrepreneurial schools, still excellent. Green.

Capital: The world’s financial hub is the #2 destination for VC investment, with $20B invested in 2020 and $39B invested Q3 2021. Green.

Infrastructure: Expensive and space-limited. Hard enough if you’re a software company, miserable if you’re a hardware company. Even New Jersey and Long Island are tough. Red.

Culture: The city is aware of and affected by climate change, but it would be hard to say climate tech is currently a significant part of the city’s culture. At Azolla, we’ve looked at more upstate NY companies than companies headquartered in NYC. Having lived there, it feels weird to ding New York’s culture, but: yellow.

Overall: Yellow.

Miami

Tech talent: This is a bet on migration. Tech companies, banks, and supporting players are opening up shop, but fewer are completely uprooting and moving there. A year ago I would have said red. Today: yellow.

Universities: There’s the University of Miami, but that’s about it. Mayor Suarez has been pitching Florida Polytechnic University to build a blockchain program. You’d have to believe that either local schools build up more climate-relevant expertise, or that other schools set up branches in Miami (like Wharton did in SF). Red.

Capital: Florida startups received $2.2B in VC in 2020 and $3.2B through Q3 2021. It’s unclear how much of that was Miami. Anecdotally, a small fraction goes to climate tech. However, some VCs are opening offices. Yellow.

Infrastructure: Office rents are middle of the pack; industrial rents are above average. Industrial space is growing rapidly. Green.

Culture: Really interesting. It’s a beautiful, fun, and diverse place. It’s on the front lines of climate change (hurricanes, extreme heat, sea level rise) and will need to adapt sooner and more dramatically than other cities. If you watch Twitter, you’d take away that there’s a booming tech culture, but it’s unclear to me how much will be lasting. On balance, green.

Overall: Wildcard with a lot of upside. I want to love Miami as a climate tech hub, but a bunch of pieces are still coming together. Yellow.

—

This is obviously not all the cities! I’m pumped to learn more. Drop me a line if you think I missed something important. Or if you want to invite me to Miami. Maybe we’ll revisit this in the future.

Honorable mention: Los Angeles (aviation, general), Chicago (industrials, general), St. Louis (agtech), Research Triangle (biotech), Austin (high tech, chemicals and materials), San Diego (biotech), Pittsburgh (electrical engineering, robotics), Atlanta (mechanical, power systems).

Health as climate adaptation

Via Axios:

Global warming is affecting people's health — and world leaders need to address the climate crisis now as it can't wait until the COVID-19 pandemic is over, editors of over 230 medical journals warned Sunday evening.

It’s interesting – at one level of course preserving human lives and well-being is sort of the point of all this worry about climate change? But at the same time, climate is such an abstract systems-level issue that it’s easy to lose sight of this. Day in and day out, for example, I’m mostly thinking about greenhouse gas emissions. And as a community, we don’t often talk about climate in terms of health (though that’s starting to change).

My armchair analysis is that this is because ~95% of climate world has focused on mitigation so far, rather than adaptation. If you focus on mitigation, your first goal is to reduce GHG emissions so that we can minimize how much we have to adapt to a changed planet. An “ounce of prevention” strategy. But if you focus on adaptation, your first goal is to continue the propagation and flourishing of the species as the planet changes around you. More of a “pound of cure” strategy. We of course need to do both, but we sure do talk about mitigation more than adaptation.

Diving into the article referenced:

The risks to health of increases above 1.5° C are now well established. Indeed, no temperature rise is “safe.” In the past 20 years, heat-related mortality among people over 65 years of age has increased by more than 50%. Higher temperatures have brought increased dehydration and renal function loss, dermatological malignancies, tropical infections, adverse mental health outcomes, pregnancy complications, allergies, and cardiovascular and pulmonary morbidity and mortality. Harms disproportionately affect the most vulnerable, including children, older populations, ethnic minorities, poorer communities, and those with underlying health problems.

Global heating is also contributing to the decline in global yield potential for major crops, which has fallen by 1.8 to 5.6% since 1981; this decline, together with the effects of extreme weather and soil depletion, is hampering efforts to reduce undernutrition. Thriving ecosystems are essential to human health, and the widespread destruction of nature, including habitats and species, is eroding water and food security and increasing the chance of pandemics.

At a high level, this is clearly bad and seems consistent with the effects of climate change. At the same time, the discussion about what to do with this information feels a little vague and muddled. I wish we were clearer about that. The rest of the article advocates for greater emissions cuts, rich nations aiding poor nations, funding on the scale we’ve seen for Covid-19, and the like – not to sound callous, but the usual stuff.

On the one hand, cash transfers from rich to poor nations make sense. They may be politically challenging, but giving material aid to affected people seems like a direct, effective thing to do.

On the other hand, reducing emissions as an adaptation strategy strikes me as ineffective. I know it’s all connected and we need to address root causes, but this feels like trickle-down climate adaptation. Emissions did contribute to these problems, but it was over decades and mediated through complex atmospheric systems. Cutting GHG emissions would take (order of magnitude) about as long to resolve those problems.5 It just wouldn’t be my first priority in addressing health issues caused by climate change.

I also doubt reducing emissions is what those most affected by climate change would want right away? Given a limited budget and timeframe for climate adaptation aid, say $1B, is it more effective to purchase 1 million air conditioning systems for at-risk families, or sequester 2 million tons of CO₂? I have to think the former.

Zooming out, I suppose I may not be the target audience for this piece though. This piece came out right before COP26, the annual international climate meeting for policymakers and other people above my pay grade. Maybe this article would be more surprising or motivating to the type of person that has a role at COP26.

However, it does reframe a few technology categories as adaptation tech,6 which is something that’s been on my mind a while.

Take the threat of crop declines. We might address this threat by developing drought-, heat-, and salt-tolerant crops. I’m sure this is happening already inside big ag companies and startups nipping at their heels. But now, in this light, it’s climate adaptation. Given how much money has poured into climate tech recently, and how quickly startup valuations have risen, maybe this new light means investors might value the same technology more highly? It used to be humble agricultural biotech, but now it’s one of the hottest sectors in VC.

Or take adverse mental health outcomes. If you’ve ever listened to a podcast, you’ve probably heard ads from therapy startups like BetterHelp. Maybe they’ll launch climate despair practices and we’ll call that climate adaptation?

This slope is starting to feel pretty slippery. All of these links to climate are valid and important, but I’m not sure where to draw the line, or if drawing a line is an important thing to do. Maybe the solution is a Matt Levine-style running bit called “everything is climate change.”

Elsewhere:

Worth the NYT subscription on its own: Post-mortem of the Surfside condo collapse

Long read: Maine’s lobster industry is booming, but it will almost certainly go bust as waters warm and habitats move North

Thanks for reading!

Please share your thoughts and let me know where I mess up! You can reply directly, leave a comment, or find me below:

By the way, ARPA-E is frequently hiring, and the 2022 Summit is in March. See you there? (They’re not paying me to say this.)

Or you could reduce meat demand. However, I haven’t seen any evidence that rich nations can or will cut down meat consumption at a meaningful scale. Even India, the most vegetarian nation by a long shot, is 60-70% meat-eating. Would love to be wrong about this. Let me know if you’ve got the goods!

In principle, meat can be cultured with dramatically reduced emissions compared to livestock. Last I looked, estimates were all over the place and the jury was still out. For the sake of argument, let’s assume it pans out.

Cutting non-GHG emissions, like PM2.5, NOₓ, and SOₓ, on the other hand, would save lives and improve health outcomes quickly.

Someone is going to coin the buzzword “adaptech” in the next few years and it’s going to stick. Maybe I just did? I hate it already.